The story of a renaissance

Four centuries of history and multi-layered architecture

The architecture of the BnF’s Richelieu Site is truly multi-layered. At the heart of Paris’s 2nd arrondissement, its vast rectangular form contains some of Paris’s most unique buildings. Bordered on the east by Rue de Richelieu where number 58 contains its main entrance, to the north it dominates the little Rue Colbert and to the east it opens onto Rue Vivienne. To the south, via Rue des Petits-Champs it extends as far as the busy place des Victoires and the avenue de l’Opéra. For a long time, the complex has been referred to as the “Richelieu Quadrangle”. Ever since the market gardens that occupied the location were replaced by buildings, the site has continued to inspire some of France’s most famous architects. The space has inherited the plot’s general layout and the main lines of this rectangular grid; subsequent generations linked up its various elements, preserved existing structures and filled in empty spaces. As the Mazarin Palace in 1643, and the East India Company in 1719, the occupation of this location remained fragmentary; it gradually became a public building with the establishment of the King’s Library in 1721, the Stock Exchange in 1724 and the Exchequer in 1793. This composite complex was unified during the 19th century, whilst at the same time retaining traces of its genealogy.

The Mazarin Palace

The Hotel Tubeuf, the Richelieu site’s oldest section

The Mansart Gallery – Pigott galery

In 1644, Mazarin entrusted his first major expansion project to the architect François Mansart who updated its classical architecture and constructed a brick and stone wing at the back of the Hôtel Tubeuf, along the Rue Vivienne garden. This new building consisted of two superimposed galleries, now the Mansart and Mazarin galleries, which served as a showcase for the art collection of the Cardinal who was then one of Europe’s greatest collectors. The lower gallery was intended for antique statuary.

The Mazarin Gallery

The upper gallery was reserved for the most beautiful pieces in his collection, such as Correggio’s The Mystical Wedding of Saint Catherine of Alexandria, currently housed in the Louvre Museum. The settings were entrusted to Italian artists including Giovanni Francesco Romanelli who painted the upper gallery’s vault frescoes in 1646–1647. This gallery’s vault has a surface area of 280 m² and is punctuated with gilded stucco compartments and scenes painted by Italian artists; it dates from the 17th century. Its iconography was inspired by Ovid’s Metamorphoses. The entire gallery underwent exemplary restoration in 2018–2019; this revealed around fifty modesty veils scattered throughout the vault’s frescoes, which were probably added in the 1660s. Only four of those veils are original and were preserved to make the vault look more like its original design.

A library within a palace

In 1721, the first of the Royal Library’s prints arrived at the Mazarin Palace and were installed in the western half of the buildings that the King had decided to make available to the Bibliothèque. These removals, unnoticed at the time, marked the beginning of the inseparable histories of the Bibliothèque and the Palace which was to become the Bibliothèque Nationale de France’s “Richelieu Site”.

Soon after its establishment within the Palace, the Bibliothèque was already short of space. Abbot Bignon, the King’s librarian, then asked Robert de Cotte, the King’s architect, to carry out the first modifications. De Cotte created three separate rooms on the Great Gallery’s upper floor along Rue de Richelieu, and completed the east wing of the main courtyard, where in 1735 he established a new gallery, the current Manuscripts and Music Reading Room. Behind this new wing, he also built the Pavillon des Globes, which several years later would house Coronelli’s great globes, now on display at the François-Mitterrand site. This work was continued by the architect Jacques V Gabriel, who built the main courtyard’s north wing and designed the Cabinet du Roi (King’s Cabinet). Despite such modifications, there was still insufficient space since the collections were continually growing.

The Louis XV salon

The medal cabinets and table were made in 1742 by the Verberckt workshop, one of the most renowned of the time. The mural decoration consists of a set of paintings representing the muses and their protectors, executed by the greatest artists of the time, who had their studios within the Royal Library. François Boucher painted the four door tops in 1742. The three trumeaux – panels located between the windows – were painted by Charles Natoire in 1745; the three on the opposite side are the work of Carle Van Loo, completed in the same year. Two large majestic portraits, copies of works by Hyacinthe Rigaud, complete the set: a contemporary copy of a portrait of Louis XV, painted in the royal workshops, and a copy of the 19th-century portrait of Louis XIV. The gilded wooden frames of the paintings also date from the 18th century.

A palace overwhelmed by its collections

From the middle of the 18th century, the Royal Library (the “Bibliothèque”) was faced with an increasing lack of space. In 1785, as an attempt to meet this challenge, the King’s architect Étienne-Louis Boullée proposed an ambitious project which was never completed. It heralded a modern library, with a large reading room and a central area housing the collections. Unfortunately, the Bibliothèque was subject to major delay. The seizure of property during the French Revolution caused its collections to increase dramatically: they doubled within twenty years, but the Bibliothèque did not gain any space. And collection was ongoing…

The few additional buildings that the Bibliothèque managed to annex, such as the Mansart Gallery and the Tubeuf Hotel, did not provide sufficient space for its ever-increasing collections. Following thirty years of hesitation regarding the potential relocation of the Bibliothèque, in 1857 the Commission – chaired by Prosper Mérimée – finally decided that it should remain at its location and to undertake major works which were entrusted to the architect Henri Labrouste.

Labrouste or the birth of a modern library

Under the architect Henri Labrouste’s impetus, the Bibliothèque embraced modernity with a new concept that physically separated the conservation (storage areas), consultation (reading rooms) and staff service (entrance hall and auditorium) spaces. Labrouste’s constructions thus reflected the need to rationalise the collections’ management and conservation. The central storage area supplied the great Workroom, currently the Labrouste Room, initiating the principle of concentration and centralisation in the storage of printed collections. Contrary to his predecessors, Labrouste no longer sought to adjust the Bibliothèque to fit the Mazarin Palace. On the contrary, he wanted to make the Palace into a real modern library and give it a strong urban identity, even if this meant demolishing a section of the historic buildings such as the Hotel de Nevers’ Great Gallery. He created the site’s current layout, which is centred on a north-south axis.

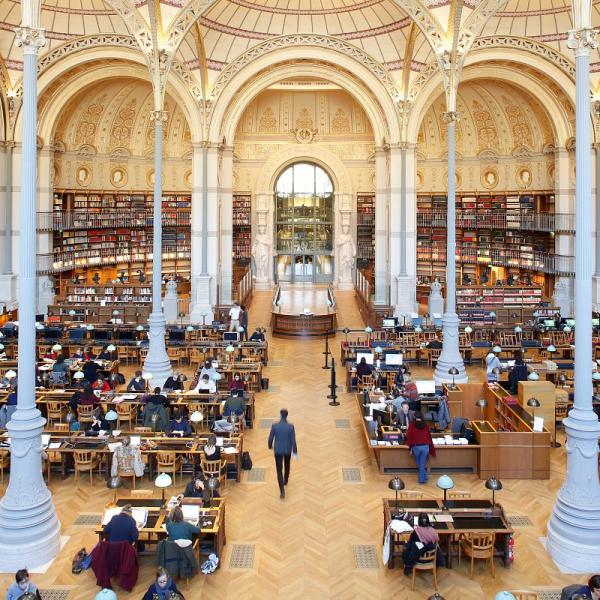

The Labrouste Room

The Labrouste Room has been a listed historical monument since 1983. Built between 1861 and 1868, it is the masterpiece of architect Henri Labrouste. Since 2016, it has been the reading room of the Institut national d’histoire de l’art (INHA – National Institute for the History of Art).

Domes of the Labrouste Room Labrouste Room The renovated Labrouste Room Seats within the Labrouste Room dedicated to the department of Prints and photography

The architect used the concept of a metallic structure, which had been tested for the Sainte-Geneviève library; here it is reminiscent of the Byzantine East. The room is illuminated by nine cupolas clad with glazed ceramic tiles that radiate uniform light throughout the room. They sit on openwork iron arches resting on 16 slender cast-iron columns, and contribute to the extraordinary impression of lightness produced by this space. The room’s perimeter is adorned with 36 medallions awarded to men and “one woman” of letters from all over the world, such as Homer, Cicero, Saint Augustine, Cervantes, Shakespeare, Corneille, Racine and Madame de Sévigné.

When it opened in June 1868, the room offered readers all modern comforts. For the first time, they had access to a heated room, with pipes passing below each table, heating their feet! Each seat was also equipped with a coat hook and an inkwell.

However, artificial gas lighting was prohibited, to avoid any risk of fire. Opening hours therefore varied throughout the year, since they depended on daylight.

The relentless pursuit of space

Jean-Louis Pascal and the Oval Room

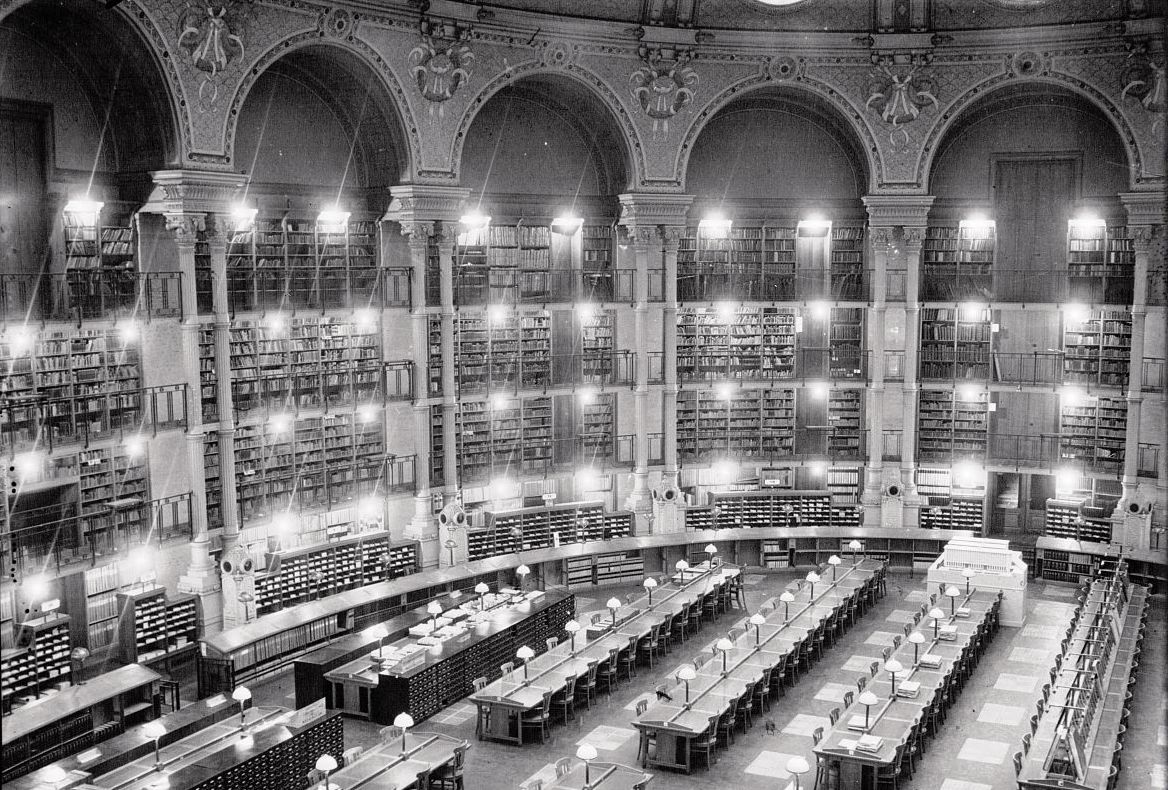

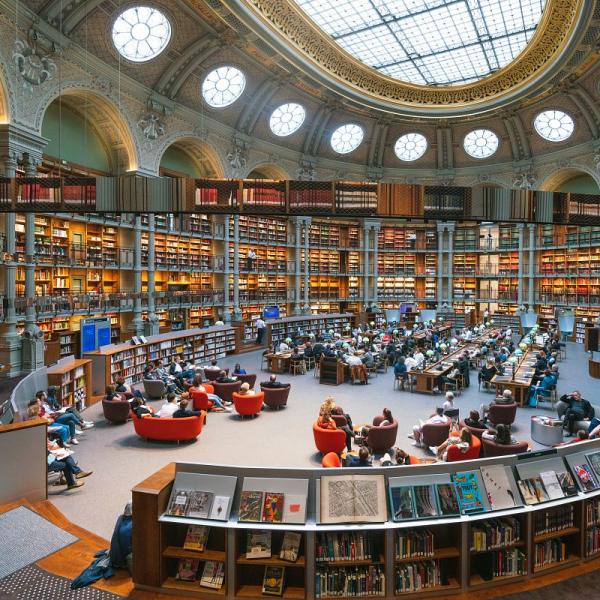

Despite the major works completed by Henri Labrouste in the 19th century, the Bibliothèque was still unable to meet its need for more space, due partly to the sharp increase in legal deposits – since 1537, copies of all documents published within France had to be deposited with the Bibliothèque – and to the mass arrival of periodicals and the press, and also to the creation of specialised departments such as Manuscripts and Prints, which were not yet equipped with modern consultation facilities. In 1874 Léopold Delisle became the Bibliothèque nationale’s new administrator; he pursued the institution’s modernisation policy and instructed the architect Jean-Louis Pascal, Henri Labrouste’s successor, to complete the main courtyard and furnish a new reading room for the Department of Manuscripts. The conquest of the “Quadrangle”, i.e. the group of buildings that currently constitute the Richelieu Site, culminated with the acquisition in 1882 of the last buildings in the north-eastern quarter, at the corner of Rue Colbert and Rue Vivienne, and their replacement with new buildings which included the Oval Room. The Bibliothèque was now separate from the surrounding buildings.

Bibliothèque nationale – Section following the Oval Room’s main axis The Oval Room’s inauguration in 1936 The Oval Room following its restoration Architectural decor, a mosaic in the Oval Room

Michel Roux-Spitz

After Jean-Louis Pascal, and under the leadership of the administrator Julien Cain, it was Michel Roux-Spitz’s turn to pursue the modernisation and modification of the site, in order to accommodate its ever-expanding collections. From the 1930s onwards, he embarked on an ambitious programme to densify the “Quadrangle” from top to bottom, a genuine “interweaving” of the architecture within the existing buildings. He densified the central storage area’s historic floors built by Labrouste, developed new basement levels, and restructured the Hotel Tubeuf for the Department of Prints and Department of Maps & Plans. Finally and dramatically, in 1954–1955 he raised the central storage area by giving it five more floors. Despite such works there was still a lack of space, and options for the densification of the “Quadrangle” were now reduced: in the 1970s, legal deposit arrivals reached three kilometres per year. The Bibliothèque was drowning.

The future of the Richelieu site

The story of the Richelieu Site’s renovation project began at the same time. Once the decision had been taken to transfer the entirety of the Departments of Printed Materials and Audiovisual’s collections to the new site, inevitably there arose the question of the necessary and profound reorganisation of the Richelieu Site and the collections destined to remain there: performing arts, maps & plans, prints, manuscripts, coins & medals, music and photographs. The decision to dedicate the Richelieu Site to the History of the Arts and Heritage was quickly taken. In addition to the BnF’s specialised departments, the Library of the Institut national d’histoire de l’art (INHA – National Institute for the History of Art) and the Library of the École nationale des chartes (National School of Charters) were gradually taking up more space.

The 1970s and 1980s were difficult years for the Bibliothèque which, with limited means, was struggling to cope with the demands imposed by conservation as well as its readers. A report presented in 1987 by Francis Beck, a former Director of General Administration at the Ministry of Culture, revealed the severity of the situation, and launched initial discussions regarding the construction of a “second” Bibliothèque nationale in April 1988. On 14 July 1988, President François Mitterrand announced “the construction and development of the largest and most modern library in the world”. His announcement surprised everybody, and it was not yet known whether the project concerned the Bibliothèque nationale. In fact, another public institution, the Bibliothèque de France, was created to carry out the “Très Grande Bibliothèque” (“Very Large Library”) project; its programme was yet to be specified: for which audiences and which collections was it intended?

In August 1989, the project proposed by Dominique Perrault, a young architect who was relatively unknown at the time, was chosen by François Mitterrand following an international competition. On 3 January 1994, the Bibliothèque nationale and the Bibliothèque de France became the Bibliothèque nationale de France (National Library of France).

The scale of the new site, which was named the François-Mitterrand Site, was impressive. On a 7.5 hectare plot at the heart of the 13th arrondissement stand four towers, each comprising 22 floors; they enclose a 9,000 m² garden. The site provides over 200 linear kilometres of depositories. Altogether there are 4,000 seats in the public library – which opened its doors to all readers aged 16+ in December 1996 – and the research library, which opened in October 1998 and is reserved for researchers. The Bibliothèque has come to be epitomised by this architecture.

Twenty-five years later its story is ongoing, with the prospect of opening a new conservation site and National Press Conservatory in Amiens.